The West Leederville Way

Pedagogical approaches

PEDAGOGICAL APPROACHES

‘The West Leederville Way’ pedagogical approaches have been chosen as they are evidence-based, high impact teaching strategies. While these approaches will not look exactly the same in every lesson, evidence suggests they work well in most, and our teachers are encouraged and supported to apply these strategies across all learning areas.

Selecting from approaches that range from thinking strategies to effective technology integration, our teachers design learning experiences that cater to the wide variety of learning needs that our students present each day. The use of consistent approaches and strategies ensures our students can seamlessly move from lesson to lesson, teacher to teacher, and year to year, with confidence.

Visible Learning

Much of the WLW is underpinned by the well-known Visible Learning research of John Hattie. His most recent research synthesises 1400 meta-analyses relating to the influences on achievement in school-aged children. It presents the largest ever collection of evidence-based research into what actually works (and doesn’t work) to increase student achievement. He uses effect sizes to compare the impact of many influences on student achievement, where an effect size of 0.4 represents one year’s growth over the course of one school year. An effect size of greater that 0.4 indicates the potential for accelerated achievement.

The staff at WLPS understands the factors that have the highest impact on student achievement. They use this information to contribute to strategic decision-making around the future directions of the school, when collaboratively developing and refining whole-school plans, and when planning lessons. Some of the top influences from Hattie’s studies, their most recent effect sizes, and a summary of how they are incorporated into the WLW include:

RTI is the provision of early, systematic assistance to children who are struggling in one or many areas of their learning. When a student does not respond to assistance, it may trigger the need for an evaluation to determine if the student qualifies for special education services.

WLPS has very comprehensive systems in place to:

- provide quality differentiated teaching practice to all students,

- identify students who may be at educational risk,

- provide targeted intervention to students at educational risk,

- secure disabilities allocations, and

- appropriately resource classes.

At WLPS, teachers often involve entire classes in discussions. This creates opportunities for:

- students to improve their communication skills

- students to learn from each other

- the teacher to gauge student understanding (a form of formative evaluation)

- the teacher to provide feedback and to correct misunderstandings/errors

Collaborative learning structures may be used before whole-class discussions to help to create a safe environment for sharing and to encourage greater participation.

Teacher clarity is the organisation, explanation, examples and guided practice, and assessment of student learning. In Hattie’s Visible Learning text, an example of teacher clarity is the clear statement of learning goals and success criteria.

This is a key feature of West Leederville’s explicit teaching approach and implementation of the Gradual Release of Responsibility model. This approach also includes worked examples, guided practice, and the provision of immediate feedback and correction. All of these elements are essential to teacher clarity.

Teachers should give feedback on task, process and self-regulation, rather than praise (which doesn’t contain any learning information).

Effective feedback:

- is clear, purposeful, meaningful and compatible with prior knowledge

- is focussed on the learning intention and success criteria

- occur as students are doing the learning; therefore, verbal feedback is much more effective than written

- provide information on how and why the student has or has not met the criteria

- provide strategies for improvement

According to Hattie, feedback is useful when it addresses the fundamental questions of “where am I going?”, “how am I going?” and “where to next?” These questions are powerful as they reduce the gap between where the student is, and where they are meant to be, in reference to their learning goals. Another form of powerful feedback is that sought by the teacher – where students show the teacher what they have learned (formative assessment).

As part of our explicit teaching culture, teachers regularly provide instructive feedback during the ‘we do’ and ‘you do’ phases. Importantly, explicit instruction often emphasises the positive function of errors – when teachers make immediate corrections to ensure achievement of learning goals. This type of ‘error training’ can lead to higher performance in classrooms if the teacher has created a safe environment in which students are comfortable in taking risks.

Teachers also use student assessment data, and seek feedback from students in lesson plenaries, as a source of feedback on the effectiveness of their teaching practice. Feedback is also sought from students in our 360 degree performance improvement process.

In the school’s 2017 IPS Review Findings, the reviewers stated: “Discussions with student leaders showed that the setting of achievement goals and the ongoing provision of feedback from teachers about their performance was having a powerful and positive impact on their learning”.

Learning intentions are descriptions of what learners should know, understand and be able to do by the end of a learning period or unit (AITSL). In addition to learning intentions, students may also have individual learning goals.

Learning intentions are most effective when:

- they provide students with an appropriate level of challenge

- they are matched to activities and assessment tasks

- students share a commitment to achieving them (as they are more likely to seek feedback)

- they are referenced throughout the lesson, and not just at the beginning or the end

Students at WLPS set goals in many aspects of their learning. In addition, as part of our explicit teaching approach, teachers regularly set learning intentions and use these to:

- ensure all students know what they are going to learn

- provide a basis for feedback

- track and assess progress

- help teachers to gauge the impact of their teaching

- refer to explicit instruction section

Phonics is specialised instruction that enables beginning readers to crack a complex a complex alphabet code, English. Cracking this code effectively frees up resources for comprehension.

Evidence supports the implementation of explicit and systematic phonics instruction that focuses on developing a sound and deep understanding between the arrangement of the letters in a word (spelling) and its pronunciation (decoding).

Systematic phonics programs help students understand why they are learning the relationships between letters and sounds, teach in a logical and progressive sequence and support student application of phonic knowledge as they read and write. Phonics instruction is necessary but not sufficient. It is important to teach deep orthographic knowledge about morphemes and rules.

At WLPS, a synthetic phonics program called Letter and Sounds is taught from Kindergarten to Year 2. This program builds children’s speaking and listening skills in conjunction with their phonemic understandings to prepare them for learning to read. It sets out a detailed and systematic program for teaching phonic skills for children.

From Year 3 to Year 6 the chosen spelling program is Words Their Way, a teacher-directed, student-centred approach to vocabulary growth and spelling development whereby students engage in a variety of sound, pattern and meaning activities, sorting pictures and words. This program caters for differentiated learning in the classroom.

The purpose of scaffolding is to simplify tasks and reduce the cognitive load when a student is not yet able to perform the task. Scaffolding provides support and may take the form of:

- the provision of knowledge

- the demonstration of strategies

- modelling

- questioning

- instructing

- offering feedback or correction

- restructuring a task

At WLPS, scaffolding is inherent in our use of the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model and explicit teaching. Many of our chosen whole-school programs also provide high levels of scaffolding. Teachers may plan to use scaffolds when they are designing lessons, or flexibly implement them when a point of need is identified during a lesson.

Thinking Skills

The use of thinking skills is a key component of the WLW. Visible thinking, critical and creative thinking, and higher-order thinking skills are explicitly taught and embedded across the learning areas. We strive to develop learners who are intelligent thinkers.

Visible thinking refers to any kind of observable representation (for example, graphic organisers) that records and supports the development of students’ ongoing learning, including their thoughts, understandings, questions, reasons, and reflections. Some of the key benefits of visible thinking include:

- a deeper understanding of content

- an increased motivation for, and engagement with, learning

- the development of ‘thinking skills’ – students’ understanding of how they think and learn (metacognition)

- an ability for the teacher to see learning through the eyes of the students (visible learning)

- increased opportunity for formative assessment and the provision of feedback

To promote visible thinking, teachers at WLPS weave thinking routines through their classroom curricula. These routines help students to make their ideas visible and accessible, and provide them with ways to help structure their ideas and reasoning. A number of these routines are also co-operative learning strategies. Examples include: Think Pair Share, Venn Diagrams, Mind Maps, KWHL Charts, Jigsaws, 3-2-1 Graphic Organisers and Plus Minus Interesting.

The effect sizes related to the implementation of metacognitive strategies, such as thinking routines, include:

- metacognitive strategies 0.60

- self-questioning 0.64

- classroom discussion: 0.82

- concept mapping: 0.64

- the ‘Jigsaw’ routine 1.2

Importantly, the use of thinking routines helps to make student learning visible – where teachers can ‘see’ what students are learning. This has a number of associated benefits, including providing teachers with information to:

- diagnose students’ immediate needs or necessary interventions

- decide ‘where to next’

- immediately offer support and/or feedback

At WLPS, students develop critical and creative learning skills as teachers explicitly teach and embed the skills throughout the learning areas in independent and collaborative tasks. The staff uses ACARA’s Critical and Creative Thinking learning continuum to plan integrated tasks, and programs such as Habits of the Mind to explicitly teach the skills.

Critical and creative thinking is a general capability of the West Australian Curriculum, which states: “Students develop capability in critical and creative thinking as they learn to generate and evaluate knowledge, clarify concepts and ideas, seek possibilities, consider alternatives and solve problems. Critical and creative thinking are integral to activities that require students to think broadly and deeply using skills, behaviours and dispositions such as reason, logic, resourcefulness, imagination and innovation in all learning areas at school and in their lives beyond school.”

Critical and creative thinking has four elements:

- Inquiring – identifying, exploring and organising information and ideas

- Generating ideas, possibilities and actions

- Reflecting on thinking and processes

- Analysing, synthesising and evaluating reasoning and procedures

The third and fourth elements of critical and creative thinking are directly linked to visible thinking, as students are required to ‘think about their thinking’ (to use metacognition). At WLPS, these elements are therefore also addressed during the implementation of ‘thinking routines’.

Some brief examples of how critical and creative thinking is embedded in some of the learning areas include:

Numeracy: choosing strategies, analysing alternative approaches to solving problems, justifying choices of strategies and employing problem-solving techniques.

Literacy: discussing the aesthetic or social values of texts, analysing points of view, sharing personal responses and expressing preferences for texts.

Science: posing questions, making predictions, solving problems through investigation and analysing and evaluating evidence.

Technologies: analysing problems that do not have straightforward solutions, thinking critically and creatively about possible solutions and engaging in computational thinking.

Humanities and Social Sciences: questioning sources of information and assessing reliability, examining past and present issues, developing plans for personal or collective action, thinking about the impact of issues on their own lives.

Habits of the Mind are a set of 16 life-related problem-solving skills that promote reasoning, insight, perseverance and creativity. Understanding The Habits enhances students’ abilities to select appropriate patterns of thinking when faced with a problem, uncertainty or dilemma. At WLPS, we implement this program with the aim of providing students with the thinking skills and metacognitive skills to work through real-life situations, independently and collaboratively, to reach positive outcomes. Ultimately, we aim to develop students that have the characteristics of effective thinkers.

The Habits are:

- Persisting

- Managing impulsivity

- Listening with understanding and empathy

- Thinking flexibly

- Thinking about your thinking – metacognition

- Striving for accuracy

- Questioning and posing problems

- Applying past knowledge to new situations

- Thinking and communicating with clarity and precision

- Gathering data through all the senses

- Creating, imagining and innovating

- Responding with wonderment and awe

- Taking responsible risks

- Finding humour

- Thinking interdependently

- Remaining open to continuous learning

Related effect sizes for critical and creative learning include:

- teaching problem solving skills: 0.63

- metacognitive strategies 0.60

- self-questioning 0.64

- classroom discussion: 0.82

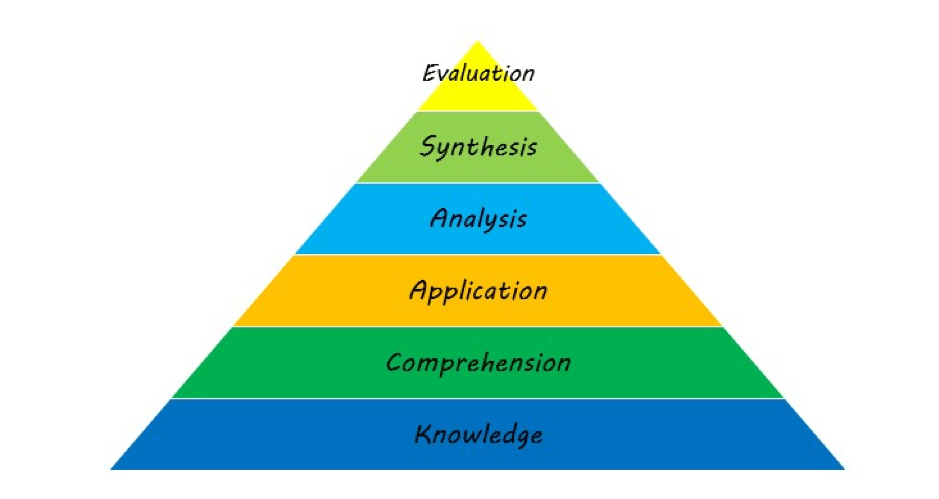

At WLPS, staff use Bloom’s Taxonomy (cognitive domain) to inform their lesson planning. This domain involves knowledge and the development of intellectual skills. The skills are categorised into six thinking behaviours and are organised from most simple to most complex. These are: Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis and Evaluation.

Teachers use the taxonomy to structure the development of the students’ thinking skills. They:

- Explicitly teach the language of verbs such as apply, define, create and critique, and the thinking required to undertake them,

- Plan classroom questioning and discussions that include higher-order thinking,

- Plan structured learning experiences that move from the simple to complex thinking behaviours, and

- Consider the thinking skills when differentiating the curriculum.

Explicit Instructions & Gradual Release of Responsibility (GRR) Model

When teachers at WLPS adopt explicit teaching practices, they clearly show students what to do and how to do it. They decide on learning intentions and success criteria, make these transparent to students, and demonstrate them using worked examples and modelling. The teachers check for understanding throughout all stages of the lesson. At the end of the lesson, the learning intentions and success criteria are revisited (Hattie, 2009). Explicit teaching has an effect size of 0.57.

Explicit instruction is underpinned by:

- the information processing model, which suggests that learners only remember what they think about and keep thinking about, and

- the cognitive load theory, which suggests that there is a limit to how much new information the human brain can process and how much can be stored in long-term memory.

Explicit instruction can be contrasted to learning that is based on constructivist theory, such as inquiry-based learning or discovery learning.

The WLW of adopting explicit teaching practices is by using the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model (GRR). This is a regular feature of most literacy and numeracy learning experiences across the school.

The goal of the GRR framework is to give students the best opportunity to successfully master new skills and strategies by providing them with appropriate levels instruction. It involves the slow and intentional shift from teacher-centred delivery to student-centred independent practice and application. It is also known as the ‘I do, we do, you do’, or the ‘show me, help me, let me’ approach.

I DO – Teachers lead instruction as students observe

This phase of the GRR involves orienting students to new material and providing them access to the new concept or skill. It may include:

- stating the purpose for learning

- setting learning goals/intentions

- making expectations and success criteria explicit

- activating prior knowledge

- modelling and demonstrations

- offering examples and explanations

- explicitly using academic vocabulary and a word wall

WE DO – Teachers guide instruction as students participate

Guided instruction is the main feature of this phase, where students are given the opportunity to master each step one at a time. Teachers may:

- lead students through differentiated practice examples, one step at a time

- encourage students to demonstrate their understanding of the new learning, under direct supervision

- provide immediate feedback and correction

YOU DO – Students practise the new skill/strategy, collaboratively or independently

In this phase, students are engaged in differentiated, meaningful activities which allow them to practise or demonstrate their knowledge of the concept and perform the skill, without assistance from the teacher. They do this independently, with partners, or in small groups. At the end of this phase, students are encouraged to evaluate their own progress according to the success criteria or learning goals and share their work.

The implementation of the GRR framework is not always linear – teachers monitor and respond to the immediate needs of students and may move back and forth between the phases as required. Use of the GRR allows teachers to teach the same concept to students but to cater for a diverse range of abilities by differentiating at the point of individual practice.

The GRR framework is not ‘scripted’.

The effect sizes that are related to explicit instruction are:

– Explicit teaching strategies – 0.57

– Appropriately challenging goals – 0.59

– Worked Examples – 0.57

– Spaced Practice – 0.60

– Teacher Clarity – 0.75

Habits of the Mind are a set of 16 life-related problem-solving skills that promote reasoning, insight, perseverance and creativity. Understanding The Habits enhances students’ abilities to select appropriate patterns of thinking when faced with a problem, uncertainty or dilemma. At WLPS, we implement this program with the aim of providing students with the thinking skills and metacognitive skills to work through real-life situations, independently and collaboratively, to reach positive outcomes. Ultimately, we aim to develop students that have the characteristics of effective thinkers.

The Habits are:

- Persisting

- Managing impulsivity

- Listening with understanding and empathy

- Thinking flexibly

- Thinking about your thinking – metacognition

- Striving for accuracy

- Questioning and posing problems

- Applying past knowledge to new situations

- Thinking and communicating with clarity and precision

- Gathering data through all the senses

- Creating, imagining and innovating

- Responding with wonderment and awe

- Taking responsible risks

- Finding humour

- Thinking interdependently

- Remaining open to continuous learning

Related effect sizes for critical and creative learning include:

- teaching problem solving skills: 0.63

- metacognitive strategies 0.60

- self-questioning 0.64

- classroom discussion: 0.82

Co-operative Learning

Co-operative learning is a social instructional strategy which enables teachers to create rich and varied learning environments. It occurs when students work in small groups and all participate in a learning task by actively negotiating roles, responsibilities and outcomes. Co-operative groups have five elements: positive interdependence, individual accountability, face-to-face interaction, social skills and processing.

The WLW encourages teachers to incorporate a range of co-operative learning structures into all learning areas, to carefully engineer student interactions for learning – to ensure they are effective co-operative groups. Some examples of the co-operative structures used include: think pair share, say and switch, round-robin, three-step interview, corners, graffiti, and jigsaw. As WLPS students are familiar with the function of the co-operative learning structures, the time taken to explain them is minimal.

Research demonstrates that the effective implementation of co-operative learning can result in higher self-esteem, higher achievement, increased retention, greater social support, more on-task behaviour, greater collaboration and development of collaborative skills, greater intrinsic motivation, increased perspective taking, better attitudes towards school and teachers, and the use of higher level reasoning (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec 1990).

The effect sizes related to co-operative learning include:

- Jigsaw method 1.2

- Peer tutoring 0.53

- Reciprocal teaching 0.74

- Small group learning 0.49

- Co-operative learning v whole class instruction 0.41

- Co-operative learning vs individual work 0.55

- Co-operative learning vs competitive learning 0.54

Collaborative Team Teaching

Collaborative team-teaching at WLPS is an approach to curriculum delivery where two teachers, often with timetabled EA assistance, share teaching responsibilities within a classroom setting. Collaborative team-teaching is a long-standing approach to teaching and has been practised in many schools, for many years.

Collaborative teaching at WLPS is always done by choice. If teachers choose to teach collaboratively, they will use their professional knowledge to contextualise their teaching program to suit their students and the curriculum. They may teach collaboratively in just one or two learning areas, or open the doors between their classrooms to create a larger ‘open classroom’. When collaborative team-teaching occurs, the ultimate responsibility for curriculum delivery, assessment and reporting of all students within a form group still lies with the individual teacher of that form class.

The success of collaborative teaching is dependent on the teachers, their ability to provide support for each other, the compatibility of their individual teaching styles and strengths, and their use of common approaches to teaching. It is for these reasons that collaborative teaching is often a choice our teachers make, if they are teaching in a year level with a ‘compatible’ colleague.

Teachers at WLPS believe that the benefits of collaborative team-teaching may include:

- the opportunity to work in close collaboration, further to the opportunities that can be provided by the school in the form of Phase-of-Learning meetings and collaborative planning time,

- the ability to use learning spaces more flexibly,

- more flexibility with student groupings and an enhanced ability to differentiate the curriculum. This, in fact, results in more contact with a teacher – especially when students are arranged into ability groups,

- the ability to use different models of teaching,

- the greater opportunity to learn from a colleague/to provide feedback – especially if the teachers have different strengths. Ultimately, if teachers are paired effectively and schools have a strong performance-improvement culture (which WLPS does), this can result in improved teacher performance.

- more continual, rigorous student assessment/diagnosis of learning needs and excellent moderation practices. This includes constant informal discussions about student needs/progress.

Other benefits include:

- Students act more cooperatively with others, students are exposed to the views of more than one teacher (Goetz, 2000).

- The variety of teaching approaches used by the team-teachers can reach a greater variety of learning (Brandenburg 1997)

- The cooperation that the students observe between team teachers serves as a model for teaching students positive teamwork skills and attitudes. Benefits of team teaching include higher achievement, greater retention, improved interpersonal skills and an increase in regard for group work for both students and teachers (Robinson and Schaible, 1995)

- Team-teaching provides opportunities for teachers to work differently in teams to collectively address diverse learners’ needs (Mackey, O’Reilly, Jansen & Fletcher, 2016)

- Attention to developmentally appropriate educational experience at all age levels, and the development of high order technological skills with interactive media cannot be achieved effectively within an isolated, individualised teaching model (Leggett & Hoyle 1987; Purkey & Smith, 1983; Rosenholtz & Kyle 1984)

- Teachers who traditionally control what was happening in their own class now consider what is happening in other classes and benefit from exposure to flexible classrooms (Bergen, 2012).

Technology Integration – the SAMR Model

As a Technologies Teacher Development School (TDS), WLPS prides itself on the effective integration of technologies, including iPads as part of the BYOD program.

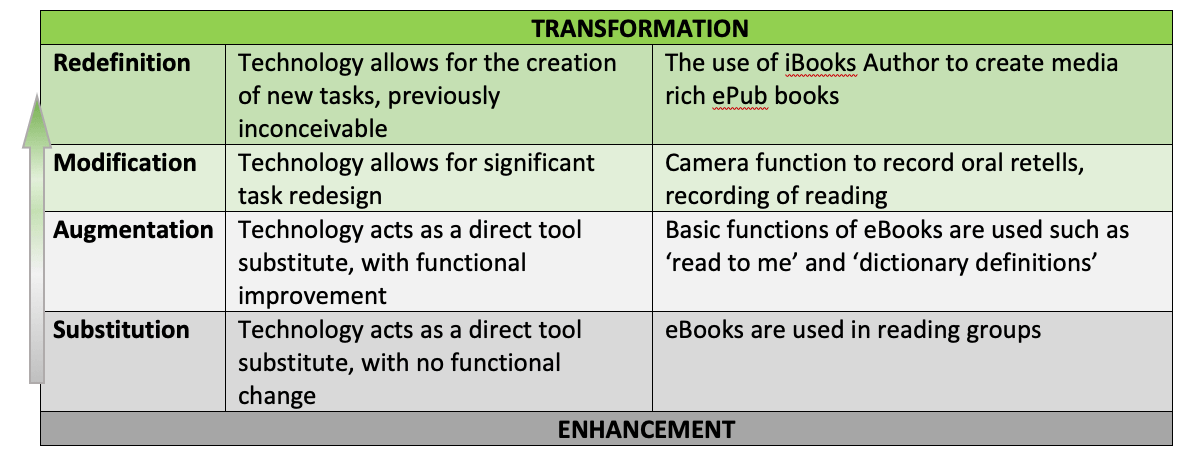

A key feature of the WLW is the use of the Substitution, Augmentation, Modification and Redefinition (SAMR) model. This model is a four-level approach for selecting, using and evaluating technology in K-12 settings. It is underpinned by the premise that the mere presence of digital tools in the classroom does not result in effective technology integration.

According to the Department of Education WA, technology integration at the substitution or augmentation levels only slightly enhances student learning. Although students may be engaged while using technology, the use of the device remains defined and limited. This can be thought of as ‘using technology just for the sake of using it’. In contrast, when technology is used at the modification or redefinition levels, it can promote higher-order thinking, the use of creative and critical thinking skills, problem-solving and collaboration. Ultimately, technology integration in the two highest phases results in transformational learning.

At WLPS, teachers aim to transform learning by significantly redesigning tasks or creating new tasks that were previously inconceivable. Those that are part of BYOD classrooms plan to regularly use iPads in ways that modify or redefine learning experiences. Our teachers use the SAMR model to plan for the use of technologies across the learning areas, and to critique their use of technologies.

The following table explains the SAMR continuum and provides examples as to how technology may be used at each of the different levels in a literacy program. It is courtesy of Ruben R. Puentedura, Ph.D., as cited by the DoE.

The effect sizes related to technology integration include:

- technology with students with special learning needs 0.57

- technology in other learning areas 0.55

- intelligent tutoring systems (Reading eggs, Maths Space) 0.48

- technology in writing 0.42

- technology in maths 0.33

- technology in reading 0.29